+plus+

More information

Ask your questions

Send us your questions,

Share your questions!

only one address

PureSakeisGood@gmail.com

list of questions

below

Send us your questions,

Share your questions!

only one address

PureSakeisGood@gmail.com

list of questions

below

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

01/ Qu’est-ce que le saké Junmai ?

02/ What does Junmai mean?

03/ How is sake drunk? Which sakes should be heated and why?

04/ How do you heat sake? At what temperature?

05/ How is sake stored?

06/ What is the colour of real sake?

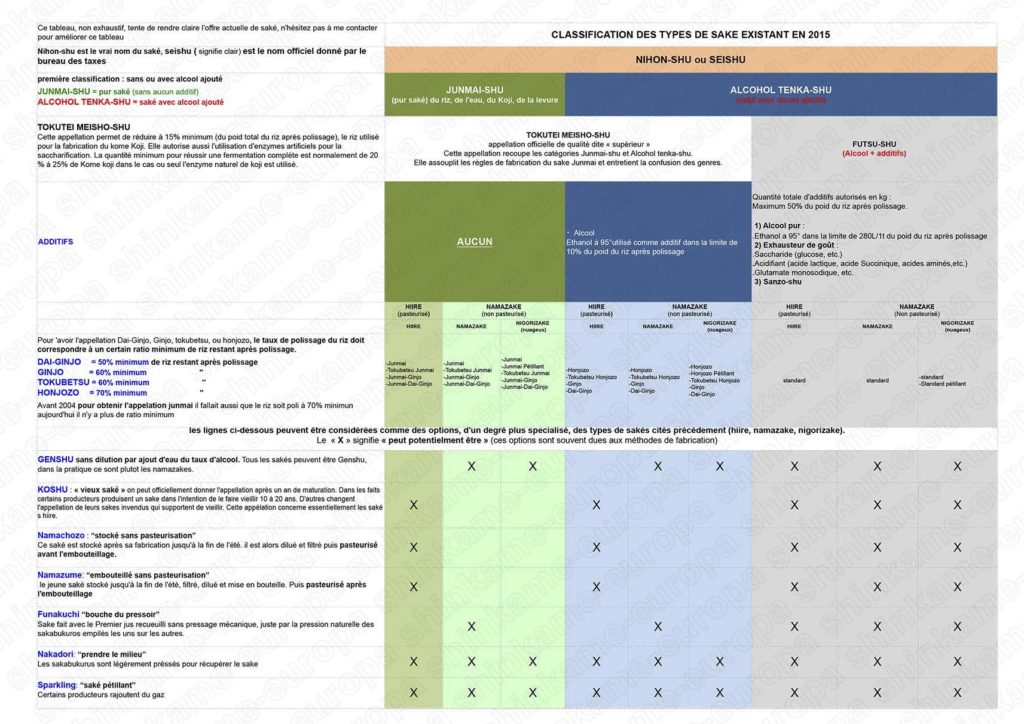

CLASSIFICATION TABLE OF TYPES OF SAKE

07/ Understanding the current state of the market

INGREDIENTS FOR GOOD SAKE

08/ Qu’est ce que le Koji ?

09/ Qu’est ce que le Kome-koji ? Quelle quantité ?

10/ Combien y a-t-il de sortes de riz à saké ? Quelle différence avec un riz alimentaire ?

11/ Quelle eau utiliser ?

12/ Les levures ?

13/ The men

HOW SAKE IS MADE

14/ Qu’est-ce que la double fermentation simultanée ?

15/ The Kimoto method

16/ The Sokujo method

17/ The Yamahai method

18/ Discussion of these 3 methods

19/ Pourquoi poncer le riz ?

20/ Pourquoi cuire le saké ? quelle est la difference avec un namazake ?

21/ Ginjo et Dai Ginjo ?

CONTEMPORARY HISTORY OF SAKE

22/ What was the quality of sake before and after World War II?

23/ Why did the traditional Junmai sake completely disappear during World War II?

24/ Why did sake with added ethanol continue to be the norm after the war until today?

25/ How did cold sake become popular from the 1970s onwards?

26/ Who revived Junmai sake?

27/ Has Junmai sake been saved?

DOCUMENTS TO DOWNLOAD

Sake making process

Table classifying the different types of sake

The struggle of Yoshimasa Ogawahara

THE PROFESSIONALS

Contact us for the price list

and other questions

puresakeisgood@gmail.com

01/ What is Junmai sake?

C’est un alcool japonais fermenté titrant entre 5° et 22°, le plus souvent autour de 15°, à base uniquement de riz, de Komekoji, d’eau, d’acide lactique ajouté ou pas et de levures sélectionnées ou indigènes. Il est traditionnellement cuit et se boit chaud. Quand il n’est pas cuit, il prend le nom de namazaké et se boit légèrement frais. Certains sakés et namazakés peuvent être troubles ; on les appelle alors Nigorizakés.

02/ What does Junmai mean?

Junmai-shu = pur alcool de riz

This means that no additives (flavour enhancers, sugar and/or distilled alcohol) have been used during the production of the sake. Its colour is slightly yellow.

Only junmai-shu sake is real sake. There is no tradition of sake fortified with distilled alcohol in Japan. When alcohol or flavour enhancers are added, it means one of two things: either the brewer has no control over his fermentation, or he wants to increase the quantity produced to reduce costs. This goes against the grain of quality sake.

03/ How is sake drunk? Which sakes should be heated and why?

Pour le deguster, le saké est traditionnellement chauffé (à ne pas confondre avec la cuisson qui est une étape dans la fabrication du saké dit hiire), cela va permettre d’ouvrir les arômes. Chauffer un saké, c’est un moment de vérité qui va faire ressortir les qualités et les défauts. Seuls les sakés très bien faits peuvent supporter la chauffe. Après l’avoir chauffé, on le boit progressivement, au fur et à mesure qu’il refroidit jusqu’à froid.

Les namazakés, comme ils ne sont pas cuits, se boivent eux plus volontiers à température ambiante ou légèrement fraiche.

There are no strict rules for tasting sake. Often it is the match with the food that will determine what to do. If there is only one strict rule, it is this: the food pairing allows everything and in the end it is always right.

Donc pour être plus souple et rester dans l’harmonie japonaise, les japonais ont horreur du conflit, je dirais « si on veut boire un sake chaud, on choisira plutot un saké cuit, si on veut boire un sake froid, on choisira plutot un saké cru dit namazake et à la fin l’accord a toujours raison

04/ How do you heat sake? At what temperature?

Dans l’idéal, le saké se fait chauffer au bain-marie, cela fait une chauffe plus douce et régulière. Le saké va être chauffé entre 45° et 70° parfois plus. Il faut d’excellents sakés pour les chauffer à cette température. Si ce n’est pas le cas, de mauvais goûts vont apparaître, souvent une mauvaise amertume en fond de bouche, ou un très fort déséquilibre dans les saveurs, ainsi que des odeurs d’alcool. En général quand le sake n’est pas d’assez grande qualité, les producteurs de ces sakés conseillent de les boire froids. Le froid, en anesthésiant votre palais, va en cacher les défauts. Si vous vouler découvrir le plaisir d’un vrai saké froid buvez plutot un namazake, saké cru.

05/ How is sake stored?

Before opening, il faut le garder à l’abri de la lumière à une température de cave ou n’excédant pas 20°. Dans ces conditions, un bon saké va se garder plusieurs années et s’améliorer. Il va gagner en arômes, en finesse et en profondeur. Si vous voulez le garder beaucoup plus longtemps 10, 20 ou 30 ans certain sakés nécessiteront d’être garder à une température proche de 0° voir négative. le froid ralentit le vieillissement du saké.

After opening, it can be kept at room temperature for several months or even years. In any case, for long storage, it is preferable to protect the sake from UV rays and high temperatures. In general, a well-made sake is capable of withstanding sometimes surprising conditions, including namazake.

If the sake does not keep before or after opening, it speaks about its quality and also about the skill of the brewer.

06/ What is the colour of real sake?

The true colour of sake is slightly yellow. When sake is without colour, it is because it has been filtered with activated charcoal to remove the colour and bad taste this is totally mass production way. As it ages it will turn amber to black.

07/ Classification of the types of sake on the market

See table below, you need to know a little about the dark history of sake from the second world war to the 2000s to understand the current state of the market, which mixes drinks that are totally different under the same name of Seishu. In my opinion sake is junmai-shu or it is not!

08/ What is Koji?

Koji is a mould that transforms the starch contained in rice into sugar. This stage is called saccharification. It is called kojikin in sake brewery.

09/ What is Kome-koji? How much?

Once the Koji has developed on and in the rice grain and has begun to transform the starch into sugar, this rice is called Kome-koji. A minimum of 17.5% Kome-koji is required for successful fermentation. Since 2004, legislation has allowed only 15% to be used! In this case, an artificial enzyme must be used, without which it is impossible to complete the fermentation. The legislation does not oblige brewers to indicate its use on the label.

10/ How many types of sake rice are there? What is the difference with food rice?

Il y a plus de 170 variétés de riz à saké. Comparé à un riz alimentaire, le riz à saké est plus gros et à un coeur composé essentiellement d’amidon . Le roi des riz à saké s’appelle Yamada-nishiki. Il a été créé en 1934 par croisement entre deux variétés de riz, son cœur représente 35 à 40% du grain de riz. Même si Il est possible de faire du saké ave du riz alimentaire, l’intérêt d’utiliser un riz à saké est qu’on va pouvoir concentrer la teneur en amidon par le polissage en éliminant la couche extèrieur contenant une majorité de proteine et lipide.

11/ Which water should be used?

You need pure spring water. Hard water is said to be better for making good sake than soft water, as it contains more minerals that will help the fermentation process. The potassium, magnesium and certain phosphorus compounds will feed the koji and the yeast, which will become more active and spread more quickly to invade the brew, reducing the possibility of it being contaminated by other pests. In fact the brewer's experience is the most important element, whether the water is soft or hard he will know how to act to obtain what he wants whatever the conditions.

12/ Yeast

Sur les levures il y a débat ! Ce qu’il faut savoir c’est que contrairement au vin ou le raisin est juste pressé, dans le saké le riz est poncé, rincé puis cuit à la vapeur pour le rendre gélatineux, si bien qu’après toutes ces étapes le riz est débarrassé de ses levures indigènes. Traditionnellement c’était donc les levures vivant et contenues dans l’air de la brasserie qui permettaient la transformation du sucre en alcool. Le problème dans ce cas, c’est que tant que l’acide lactique ne s’est pas développé en quantité suffisante dans le fond de cuve (appelé shubo) pour protéger le jus en fermentation, des bactéries et des levures indésirables viennent occuper la place et pourraient gâter et donner un mauvais goût au saké. parfois même dans le cas où la quantité de levures est insuffisante, la fermentation ne pourra pas être menée à son terme. Aujourd’hui l’hygiénisme japonais est un frein au développement de ces méthodes utilisant les levures indigènes. Au début du siècle, les chercheurs ont réussi à isoler les levures idéales pour mener la fermentation du saké. Ce fut une révolution dans la production du saké, car cela a permis d’améliorer considérablement la qualité du saké. Aujourd’hui, il y a de nombreuses sortes de levures sélectionnées. Les plus utilisées sont les levures N° 6, 7 et 9. Pourtant récemment certaines brasseries très influencés par le mouvement du vin Nature qui est très à la mode au japon, reviennent aux levures indigènes, ces sakés sont souvent très acide, probablement par le manque d’acide lactique au début de la fermentation, parfois l’acide lactique va trop se développer ce qui va donner un goût de yaourt au saké. Mais quand le brasseur a su laisser les levures indigènes coloniser sa brasserie et qu’il maitrise ces fermentations, notemment celle du shubo, alors ces sakés à base de levure indigène appelées Kuratsuki, sont vraiment très agréables et très digestes.

ce qu’il faut retenir c’est qu’il n’y a pas de bataille entre levures indigènes et levures sélectionnées voir modernes, il faut que le saké soit digeste. une erreur actuelle des producteurs est de produire des sakés de levure, ils vont construire le saké autour des aromatiques des levures ce qui va standardiser les sakés, un bon brasseur va utiliser chaque étape de la production du saké pour construire son gout. Son saké ne ressemblera à nul autre quand les sakes de levures finiront par se ressembler tous, créant une course absurde pour avoir avant les autres la nouvelle levure à la mode.

13/ The men

More than any other drink, sake is first and foremost a complex know-how that would not exist without the work of man. There are five key words around these men and their work: Team, Knowledge, Understanding, Organisation and Pleasure. There is no good sake in the long term if one of these key words is missing in the daily life of these men.

14/ What is simultaneous double fermentation?

Sake production uses the "heiko-fuku-hakko" method which literally means "simultaneous double fermentation". The reason for using this method is that rice does not contain sugar or yeast, unlike grapes for wine. Producing sake therefore requires two processes:![]() saccharification (toka), with the enzyme (Aspergillus oryzae) of the koji which

saccharification (toka), with the enzyme (Aspergillus oryzae) of the koji which

to obtain glucose from the rice starch.![]() - fermentation (hakko) which, with the help of yeast (kobo), transforms

- fermentation (hakko) which, with the help of yeast (kobo), transforms

glucose into alcohol and carbon dioxide.

This double process is carried out simultaneously and in the same tank.

By this brewing method, the resulting sake can have a

surprisingly high alcohol content of over 20%. This method requires great skill, experience and talent.

15/ The Kimoto method ?

The Kimoto method was used during the Edo period. It involves crushing the rice during the creation of the shu-bo (yeast starter), to allow and help the koji to transform the starch into sugar. This process is called yama-oroshi. At that time, the polishing rate did not exceed 90%, and no one knew how to select the yeasts. It is therefore indigenous yeasts that allow the transformation of sugar into alcohol. Lactic acid is produced naturally, allowing a natural selection of resistant yeasts and protecting the fermenting juice from bacteria. This technique is only useful in the case of brown rice that has been polished around 80 to 90% (% of rice remaining after polishing). When the rice is polished above this level, it is no longer necessary to crush the rice to allow the koji to convert the starch into sugar. Today, legislation allows the use of pure selected yeast for the Kimoto method.

16/ The Sokujo method

Au debut de l’ère Meiji, un groupement de brasseries engagea des chimistes pour étudier les méthodes de fermentation, et inventer de meilleures machines pour augmenter le polissage. suite à leurs travaux on découvre le procédé pour sélectionner et isoler les levures, et comment fabriquer de l’acide lactique. Ces découvertes permettent de simplifier le processus de fabrication, et de mieux maîtriser la fermentation. Afin d’empêcher le développement de levures présentes dans l’air, on procède à deux opérations : on ajoute dès le départ dans le réservoir servant à créer le shu-bo, l’acide lactique melangé à de l’eau. Puis, environ 12 heures plus tard, on ajoute la levure sélectionnée, qui en occupera toute la place. C’est une révolution dans le processus, car ces deux découvertes permettent d’éviter la multiplication des levures et bactéries indésirables et incontrôlables. Cette méthode a du succès dès le départ mais va vraiment s’imposer dans les année trente avec la découverte de la levure numéro 6.

17/ The Yamahai method ?

The Yamahai method was invented after the Sokujo method which allowed a better understanding of the fermentation process. From then on, brewers wanted to improve the Kimoto method, where the rice had to be crushed, an exhausting and labour-intensive activity. Yamahai means without Yama-oroshi "not to crush the rice". With the technical progress in polishing, which allows for a 70% polishing rate, it was realised that it was no longer necessary to crush the rice, as the koji could transform the starch into sugar by itself. This method works from a polishing rate close to 90% (this is interesting, because perhaps this method could have been used as early as the Edo period); it also renders the Kimoto method useless, as soon as the rice is polished at a rate lower than 90%. By the time the Yamahai method was invented, yeast selection was known. The brewer has the choice between selected yeasts and indigenous yeasts that allow the transformation of sugar into alcohol. Lactic acid is produced naturally, however, to protect the shubo (the yeast starter) from undesirable bacteria and yeasts.

18/ Discussion about these 3 methods

Nowadays, many brewers are again using the Kimoto method with rice milled beyond 70%, which is completely unnecessary and only for commercial purposes. The idea is to benefit from the aura of a return to the purest ancestral tradition. The absurdity goes as far as producing Daiginjo (rice polished to at least 50%). These brewers even claim not to use selected yeast. In fact, if you use yeast from the air, you have no control over the quantity and quality of the yeast. The consequences are random production and quality of sake. In most cases, brewers then use selected yeasts without telling the consumers, which is allowed by law, because they cannot afford to lose their production.

In summary, the Kimoto method should only be used with brown rice, polished at least at 80% or less. Lactic acid will be produced naturally and the consumer will be told if there is an addition of selected yeast or not. (Whatever the polish level is, if the result is good and makes beautiful fusional food pairing then we should do so low profil, in sake the end often justifies the means)

Below 80% rice polishing ratio, if one wants to use a more natural method, we will use the Yamahai method which will also produce its own lactic acid, and we will tell the consumer whether we are using selected yeasts or only air yeasts. It is also important to tell the brewing context of an indigenous yeast sake. If for example a brewer uses selected yeasts for his other sakes in the same brewing place, it is likely that the yeast that will develop naturally will be the same as the selected yeast, the brewery environment is no longer neutral, it can be said that there is probably a contamination by the selected yeast of these brewing areas.

The sokujo method is the most rational method in the sense that it is easier and safer to brew sake. Naturally produced lactic acid does not affect the taste of the sake, so there is no contraindication to using separately produced lactic acid; and the use of selected yeast prevents the development of bad yeast that can spoil the taste of the sake.

Whatever the method, great care must be taken at every stage, the sake must be given time to develop, and the team must be passionate about its work. This is something that mass production will never have.

En résumé, il n’y a pas de mauvaise méthode, il y a pas de mauvais outils, l’important c’est l’intentions qu’on met pour faire le saké. Un artisan aura normalement toujours à coeur la qualité de son produit sur le rendement . Maintenant, selon Yoshimasa Ogawahara, un brasseur devrait parfaitement maîtriser la méthode sokujo, car cette méthode permet toutes les combinaisons possibles. Dès lors qu’on a compris le rôle de chaque étape, on peut ensuite jouer avec toute ces étapes pour aller où l’on veut et atteindre la constance. La constance c’est la qualité principal d’un artisan japonais, comprendre la nature dans ses différents états et savoir ce qu’il faut faire pour atteindre notre but. C’est pour ça qu’au japon le travail d’un artisan, c’est le travail d’une vie. Ensuite une fois qu’on a compris, on peut jouer avec la nature et utiliser les autres méthodes.

However, nothing should be done at the expense of the quality of this consistency, because the sake maker is first of all a craftsman and sometimes also an artist.

19/ Why do we polish rice?

The core of sake rice, called 'shinpaku', is almost exclusively

made of pure starch. The outer layer of the rice consists

of proteins, fats, minerals and vitamins.

It plays a characteristic role in the taste of sake, but can also give it

an unpleasant taste if there is too much of it.

Le taux de polissage correspond à la quantité de riz restante après le polissage. Par exemple, un taux de polissage de 60 % signifie que si l’on utilise 100kg de riz complet, ne seront conservés que 60kg après polissage. Certains sakés nécessitent un polissage jusqu’au cœur du riz ou shinpaku (cœur du grain). La taille du shinpaku varie en fonction du riz. Par exemple, pour le riz Yamada-nishiki, le shinpaku est d’environ 40% du grain entier. Pour arriver à ce taux de polissage de 40%, le temps de polissage nécessaire est approximativement de 80 heures (en-dessous de 40%, la qualité du cœur reste stable, et polir plus de riz n’apportera aucun bénéfice gustatif). Mais que signifie un taux de polissage si on ne connait pas le taux d’amidon du riz utilisé ?

20/ Pourquoi cuire le saké ? Quelle est la difference avec un namazake ?

Le saké obtenu sans cuisson est appelé ’Namazake’ littéralement « cru ». Il est obtenu juste après le pressage, il peut être micro filtré ou pas, réduit en alcool ou pas. je les préfère genshu dans leur entièreté. Les qualités d’un Namazake genshu bien fait (entier en alcool, sans ajout d’eau, entre 17°et 21° environ ) une grande présence, un nez et des saveurs évidentes, une grande buvabilité comme celle d’un vin primeur pur jus, explosion et longueur comme un spiritueux mais sans le feu.

It is a real product with character!

Pourquoi quand on a un produit avec autant de caractère, d’unicité, le cuit on ?

Déjà en quoi consiste la cuisson ? Hi-ire est l’opération qui consiste à cuire le liquide pressé (seishu) à environ 65ºC, pour en arrêter complètement la fermentation. Ce procédé est généralement réalisé en deux temps : la première fois juste après le shibori (extraction), puis une deuxième fois à l’automne, après mûrissement pendant l’été, à l’embouteillage. Avant le second hiire, de l’eau est ajoutée au saké pour régler sa teneur en alcool aux alentour de 15°. On appelle ce procédé wari-mizu (dilution avec de l’eau).

Revenons un peu en arrière. Il y a très très longtemps, à une époque ou les brasseries de la region de Kyoto Nara voulait vendre leur saké à Edo (Tokyo), le voyage du saké se faisait par bateau et les sakés le supportaient mal. les brasseries ont probablement eu l’idée d’utiliser la cuisson pour aider à la conservation du saké. Puis petit à petit les brasseries, les consommateurs, se sont rendus compte qu’en chauffant le saké pour le boire, le saké retrouvait sont corps mais sans ego, sans attiré l’attention sur lui et que quand on mangeait avec le sake des nouvelles saveur surprenantes apparaissaient.

avec le temps on a compris que la cuisson avait changé la nature du sake de dominant en serviteur, que la raison d’être du saké cuit chauffé est de vivre pour la nourriture, plus précisément pour l’accord, le saké cuit chauffé révèle sa complexité par l’accord, c’est une trinité entre la bouche, le met et le saké, qui va enfanter de 3ème saveurs, on est totalement dans un accord fusionnel. le saké fait l’amour avec la nourriture pour le plaisir de la bouche.

That's why if you really want to understand sake, you have to heat it up and eat it.

If sake is a product of Terroir, it is only through the combination with local food that it asserts it.

21/ Ginjo and Dai Ginjo ?

Ginjo sakes appeared in the 20th century with industrialisation and the progress of rice polishing techniques. New flavours appeared, more fruity and floral. Daiginjo means great Ginjo, a sort of Grail of purity, by polishing the rice more and more to reach the heart of the grain. The most used rice, the king of rices as it is called, is Yamadanishiki because it has the biggest heart of all the rices, between 35% and 40% of the rice grain, it is important to know that beyond 35%, the heart of this rice becomes homogeneous. It is therefore unnecessary to polish the rice grain further. Below 35%, it is just commercial. Ginjo sake is slowly matured by lowering the temperature to around 7°C during the entire fermentation process, but there are no official rules regarding temperature.

Rules to be respected to have the Ginjo designation:![]() polishing ratio should be less than 60% polishing (semaibuai), even less than 50% for Daiginjo.

polishing ratio should be less than 60% polishing (semaibuai), even less than 50% for Daiginjo.![]() colder fermentation temperature during the moromi stage, which results in a 10-day longer fermentation time. This makes a total of about 33 days.

colder fermentation temperature during the moromi stage, which results in a 10-day longer fermentation time. This makes a total of about 33 days.![]() more gentle pressing.

more gentle pressing.![]() greater care in the production process at all stages.

greater care in the production process at all stages.

22/ What was the quality of sake before and after World War II?

Before the Second World War, all sake was Junmai, that means pure rice, without any additives or artificial enzymes. Most of them were drunk hot. After the Second World War, all sake was made with added alcohol (ethanol) and flavour enhancers and sweeteners, as required by law. These sakes were called sanzoshu, which means "three times more alcohol with the same amount of rice", and the Japanese continued to drink them hot because it was part of the culture. But since heat brings out all the flaws, the Japanese started to drink it cold or even iced. And most of them stopped drinking it, especially the new generation who turned to beer and western spirits.

23/ Why did the traditional Junmai sake completely disappear during World War II?

When Japan entered the war, it was a country mainly composed of farmers. These farmers went off to war, which led to a shortage of rice. This shortage led to a national rice rationing policy by the Japanese government, which lasted until 1968. The government distributed the quantity of rice to each person, and the breweries were no exception to this rule. As the quantity of rice was insufficient to continue producing the quantity of sake that Japan needed, the government developed a technique with the addition of alcohol and flavour enhancer, which made it possible to produce the same quantity of sake using three times less rice: Sanzoshu was born. The Ministry of Finance then passed a decree requiring all breweries to produce 100% of their sake with added ethanol, including at least 35% of their production in Sanzoshu quality. 50% of the breweries were then closed down to become arms depots, while the others had to obey and apply the national policy. Sanzoshu sake became the norm, and it was not until almost 30 years later that any producer dared to challenge this situation.

24/ Why has sake with added ethanol continued to be the norm after the war until today?

Quite soon after the war, the amount of rice produced returned to normal, but the country, which had been totally destroyed by the American bombing, had to rebuild. Sake, unfortunately, was the main source of taxes, and there was no way that these taxes could be reduced. If the breweries had started making junmai again, the quantity of sake would have fallen, as it takes a lot more rice to make traditional sake.

The second reason why the producers did not question this way of making sake was that this technique made it possible to make sake at a lower cost and to have high margins. So the Japanese gradually turned away from sake in favour of Western spirits and beer. It was not until 1966 that a producer dared to break out of this pattern.

25/ How did cold sake become popular from the 1970s onwards?

We can't say exactly what made the market move in the first place, whether it was consumer taste or a change in strategy on the part of brewers' associations. In reality, it is often a combination of circumstances more or less spread out over time. We can therefore relate some facts. The first fact is that post-war sake was of very poor quality, and that heating it made it even worse. The second fact is the history of Ginjo sake itself, which appeared at the beginning of the 20th century as a result of technical progress in rice poloishing machin.

At the beginning of the 20th century, two associations also appeared, which created competitions. The first was an association of brewers, and the second was a government association. It was the Ginjo and Daiginjo (great Ginjo) sake, which created new fruity smells, tending towards apple or citrus fruits, that won these competitions. However, during these competitions, the sake is drunk cold. We also notice at the beginning that these particular smells of ginjo sakes tend to disappear when the sakes are heated. This is why we think that these sakes are fragile. Today, it is becoming clear that the brewing process must be mastered perfectly in order to heat a ginjo sake. Few breweries have reached this level. These Ginjo sakes were produced in very small quantities, with the aim of presenting them in competitions. Before the war, these sakes were obviously all Junmai. After the war, all sake, including Ginjo sake, contained added alcohol and flavour enhancers. So here we are again in the 60s and 70s, competitions are still held, sake during these competitions is always drunk cold, and ginjo sake always wins competitions. Consumers turned away from hot drinking sake because of its very poor quality. At the same time, sake producers realised that adding pure alcohol,( ethanol), would enhance the ginjo taste. The so-called quality production was oriented towards this type of sake, and the consumers followed, which was the glory hour of cold sake on the rock.

From the 1970s onwards, Junmai sake resurfaced after almost 30 years of oblivion. The very few producers no longer mastered the manufacturing process, which led to bad tastes in the sake. The cold and charcoal filtration techniques will mitigate these defects. As a result, junmai sake is much drier and consumers have become accustomed to a very sweet sake. It has been a 30 year battle to really revive junmaishu and to start to change the image of heated sake. Consumers and producers rediscover slowly the reasons for heating sake.

Since the 2000s, quality heated sake has made a comeback. More and more producers have reached a satisfactory level of manufacturing quality, allowing their sake to be heated. It cannot be said often enough that heat reveals quality and defects, and only very high quality sake can withstand heating and reveal all its secrets.

La seule exception concerne les namazakés, sakés crus, qu’on ne chauffe pas ou rarement et qui se boivent de préférence à température ambiante.

26/ Who revived Junmai sake?

Yoshimasa Ogawahara is the father of the contemporary traditional sake called "Junmai". While still a student, he decided that what he wanted to do was to make Junmai and nothing else. He thought before anyone else that this was the only way for sake to continue to exist in the future. If he doesn't do it, the Japanese will continue to turn away from their favourite drink, breweries will continue to close, sake production will continue to decline, and sake will disappear.

What you have to understand is that in Japan it is foolhardy to question the system alone and to oppose the group. The group is more important than the individual, it's a country where you have to be one with the group. If you oppose the group, it will try to put you back on the right track and even crush you if necessary. Yoshimasa is 20 years old when he decides that his life will be to revive Junmai sake. He is full of enthusiasm and recklessness. In 1966, while still a student, he applied to the tax office for permission to brew Junmai again. This was refused, as there was no precedent for it since the Second World War. In 1967, he applied again, in his last year of university, and for the first time since the war, he obtained official permission for a brewery to brew Junmai. The tax office allowed him to brew the symbolic quantity of 3000 litres. Yoshimasa managed to convince them that he wanted to do his dissertation on junmai, so he needed to test it under real conditions. The tax office gave him permission, thinking that after he would then follow the national policy of sake with added alcohol. Yoshimasa never stopped making Junmai, and it was a 20-year battle to gradually increase the quantities produced, at the risk of the Shinkame Brewery's existence. In 1987, the Shinkame brewery became the first brewery to brew only Junmai !

27/ Has Junmai sake been saved?

No, Junmai sake is not saved. It is a fragile ecosystem between several trades and raw materials that are also in danger.![]() Les producteurs de riz : il faut un minimum de brasseries pour que les paysans continuent à produire du riz à saké, qui est beaucoup plus contraignant à produire que le riz alimentaire. Yoshimasa estime qu’un minimum de 1000 brasseries est nécessaire. Le nombre de brasserie continue à diminuer, il n’en reste environ que 1200. Et plus grave la moyenne d’age des producteurs de riz est supérieur à 70ans.

Les producteurs de riz : il faut un minimum de brasseries pour que les paysans continuent à produire du riz à saké, qui est beaucoup plus contraignant à produire que le riz alimentaire. Yoshimasa estime qu’un minimum de 1000 brasseries est nécessaire. Le nombre de brasserie continue à diminuer, il n’en reste environ que 1200. Et plus grave la moyenne d’age des producteurs de riz est supérieur à 70ans. ![]() The Tanekoji producers, essential for the Koji to develop and allow the saccharification process, producing Komekoji. There are now only 6 companies left in Japan.

The Tanekoji producers, essential for the Koji to develop and allow the saccharification process, producing Komekoji. There are now only 6 companies left in Japan.![]() Kojibuta producers, an indispensable tool for making good komekoji.

Kojibuta producers, an indispensable tool for making good komekoji.![]() The water is also in danger, the Japanese mountains are left abandoned, losing their soil little by little, following the disappearance of the traditional wooden habitat. Today, the Japanese use reinforced concrete for buildings and synthetic materials for small prefabricated houses. Poor soils deplete water, and its flow is also less constant.

The water is also in danger, the Japanese mountains are left abandoned, losing their soil little by little, following the disappearance of the traditional wooden habitat. Today, the Japanese use reinforced concrete for buildings and synthetic materials for small prefabricated houses. Poor soils deplete water, and its flow is also less constant.

Finally, legislation on manufacturing processes favours industries, and thus mass production. This creates confusion about what quality sake is, and reduces the market for those who make real Junmai.

1/ Un label de qualité créé par le gouvernement japonais qui met au même niveau saké Junmai et saké avec ajout d’alcool : le saké est une fermentation naturelle qui permet d’atteindre naturellement plus de 20°, il n’y a pas besoin d’ajout d’ethanol.

2/ Komekoji rule: official minimum quantity 15%. What you need to know is that below 18% komekoji, you need to use an artificial enzyme to make the saccharification. These artificial enzymes are also used to control the flavours. If these enzymes are used, there is no obligation to mention their use on the label.

3/ Règles sur le polissage : elles tendent à faire croire que plus on polit le riz, plus la qualité du saké est élevée. Avant 2004, il fallait polir au moins à 70% (% du riz restant) pour faire du Junmai. Après 2004, on peut soi-disant faire du Junmai avec un taux de 100%, c’est-à-dire sans le polir. En fait, cela ne signifie pas que le riz n’est pas poli, cela permet juste de récupérer la partie qu’on a enlevée pour poncer le riz et d’en faire du Junmai. Cette règle permet aussi de broyer le riz et d’en faire du Junmai.

Thus, although the quantities of Junmai appear to be increasing, it is most likely that it is only the industrially produced Junmai that gives this impression. Mass production seeks to produce more and more, reducing costs, and has no need to maintain the sake ecosystem that is essential for breweries aiming for quality sake.

pour finir la population japonaise est en déclin, le saké étant bu essentiellement par les plus de 50 ans, le marché japonais du saké va irrémédiablement se réduire, les pires heures pour le saké sont malheureusement à venir, j’espère avoir tord.